~ Preamble: ARRIVAL ~

We snuck out of Dumfries on the early train to Glasgow, when the sun was still low in the sky. With luck, we’d arrive at our destination in under 12 hours, in time for the last crossing of the Glenelg turntable ferry, with time to coorie in for dinner at our beachside bothy. After a leisurely bougie breakfast at Outlier in Glasgow, of sourdough bread and meaty mushrooms crackling with char like the skin of grilled mackerel, we boarded the train for Inverness, a Scotch pie apiece in our pockets for the connecting journey south and west, through picturesque Plockton to Kyle of Lochalsh.

Our carefully crafted plan unravelled at Perth, when our train ground to a halt and showed no signs of moving. News dripped in by degrees – a gas leak at Inverness train station led to a local evacuation, putting paid to any possibility of catching that last ferry. Our destination can also be reached from Mallaig on the west-coast line, and since rail replacement travel is notoriously difficult with bicycles in tow, we played it safe and rerouted our journey with pouts on our faces, a four-hour time-killing operation in Glasgow on our hands, and a heaven that was just about to open. Sitting soggily nursing £7 pints of Brew Dog and margaritas from a can against a backdrop of banal 90s millennial-core music was not how we’d planned to start our week of rest and relaxation in Scotland’s healing nature.

The train to Mallaig is an epic journey, strung out over many hours like the Lord of the Rings trilogy so you can properly immerse yourself in the grandeur and minutiae of the settings. These include ancient monuments like the unending moors of Corrour and Loch Rannoch and majestic Glenfinnan viaduct, both of which have enjoyed a resurgence of attention due to appearances in popular culture, but neither of which we could make out well in the twilight of driving rain that chased us until true dusk descended. We were greeted on our midnight disembarkation in Mallaig by a cacophonous commune of herring gulls who had made nesting sites of most all vacant spaces at the station, including some of the disused railway tracks, and had made a toilet of the rest.

~ THE ROUTES ~

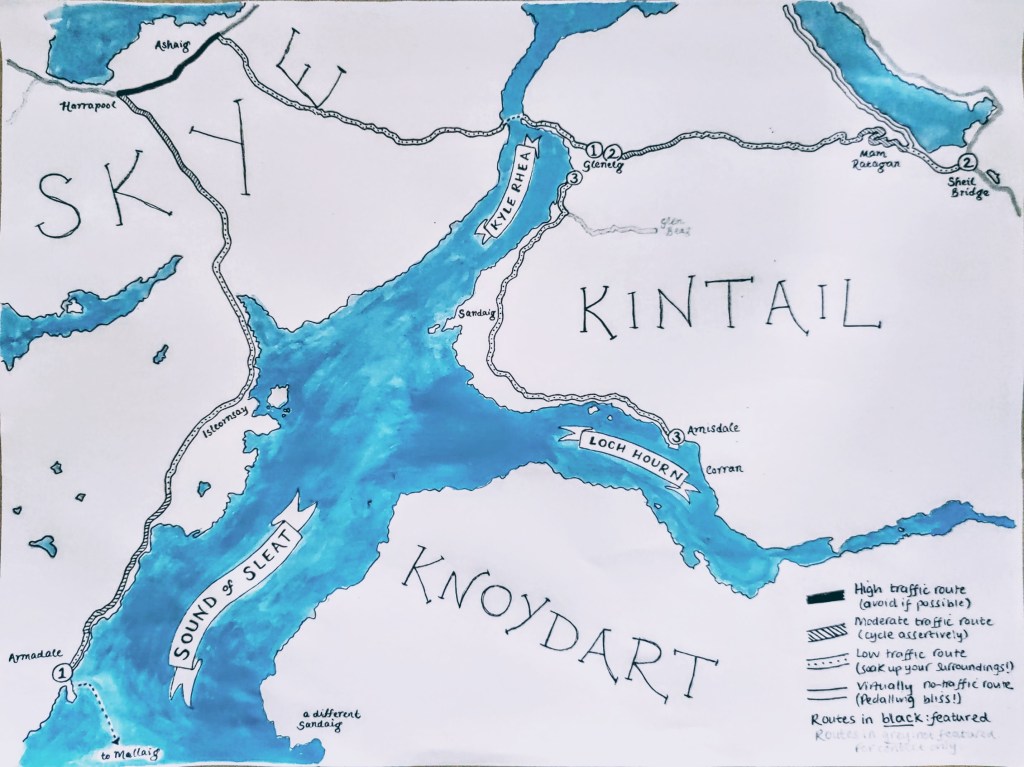

~ 1. ARMADALE TO GLENELG ~

DISTANCE 29 miles

HEIGHT GAIN c.1,700 ft

ELEVATION PROFILE

Our forced change of plan turned out to be a blessing. After a good night’s sleep unperturbed by hollering seabirds – grace perhaps of good double-glazing – and a windless ferry crossing over a glittering Sound of Sleat set alight by dazzling blue skies and blazing sunshine and with a sticky vegan cinnamon bun in hand, we set down once again on the Isle of Skye after a five year hiatus.

The Isle of Skye has a lot going for it. It’s an epicentre of Gaelic language and culture in Scotland, with place names such as Tarskavaig and Tokavaig evocative of its’ Viking past. Much of it is covered in blanket bog, a build-up of sphagnum moss as deep as seven metres in places and a substantial carbon sink; mummified in minerals and waterlogged by a basin of silted iron salts and the rainiest weather system in Scotland. It boasts a sky so unpolluted that, on a clear night the constellations leap out of the inky black so vividly that, with not too great a leap of imagination by they could act out their legends right in front of your gazing eyes.

The road from the ferry terminus at Armadale to the A87 at Harrapool is well-laid and wide and although it is lumpy it’s never too far up, or too far down. Once you’ve filled your bidons for free and stocked up on trail mix and locally-crafted edible treats from Armadale Store (there’s not a pannier bag in the world big enough for all I’d like to buy from there) there’s plenty of excursions to break up this leg, from the Torabhaig distillery and café to the quaint majesty of Isleoronsay harbour where I’ve very fond memories of wiling away a cold evening with a hearty plate of vegan Burns supper and an impromptu masterclass on whisky appreciation from a theatrical bartender. Halfway to the junction, just beyond the turn-off to Drumfearne there’s a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it slipway onto a walking and cycling route that wends through the bog in parallel to the road and is a much more pleasant way to continue your onward journey if on bike (or foot), with heather brushing at your ankles and all manner of small animals – frogs, damselflies, maybe even an adder? – that may be basking along your meander to take care for.

The next stage of the journey takes you onto the A87 towards the Skye road bridge. There are some things that Skye emphatically does not have going for it, and one is the high volume of motorised traffic, much of it tourist in nature. Skye as a Highland destination seems to have captured the international globetrotter imagination in a way that few other hard-to-reach Scottish destinations can parallel*, and the primary bottleneck for traffic on Skye is the Skye Bridge.

So I would actively discourage the cycling of the A87, save for the fact it may be the only way to get to where you want to go. (One saving grace of our enforced rail detour was that we avoided riding this road from Kyle of Lochalsh the previous evening). Watch out for tourers who are inexperienced in the external dimensions of their motorhome, and speedy Gonzalez with an overambitious travel itinerary and no time for slow-moving hold-ups (I’ll never understand why drivers in some of the most beautiful landscapes in Scotland have a tendency to try to traverse them as quickly as possible, but there you are).

Abetted by a one-way traffic management system that offered periodic reprieve from overzealous overtaking, we turned off onto Bealach Udal pass towards Kylerhea. This was a lovely road, albeit potholed in places with much loose gravel in the middle of the single-track road, requiring a bit more concentration when descending. From the Skye Bridge side the climb is long and snaking, with some short undulations and sweeping bends to catch your breath on while white-tailed eagles float on invisible thermal currents, providing a welcome distraction; taken from the Kylerhea side the gradient becomes more punishing the further you get up it, like a bleep test, until the calls of the cuckoos compete with the blood pounding in your ears and all you can focus on is the beat of your pedal strokes left and right, eagles or no eagles.

At the bottom of the road you’re rewarded with a short – uphill! – detour to a wildlife hide overlooking the Kyle Rhea strait, a narrow channel that concentrates marine nutrients and attracts a host of predators including seals, otters, cetaceans and basking sharks. The overseers of this rich and glorious ecosystem are the ‘ferry dogs’ – four working collies named Magnus, Roxie, Lumi and Spot – who accompany the Glenelg ferry on it’s frequent short passages across the strait, providing useful ‘help’ to the ferry masters. Murdoch is the saltiest of the dogs, with failsafe sea legs, a wart on his left eyelid and a blood-bloated tick nuzzled in beneath it; Lumi, the youngest and most svelte of the pack, is the most enthusiastic participant in a game of fetch on the jetty, as well as most likely to rest her head on your outstretched legs on the car deck and have a snooze during the crossing. Then there’s Spot, who invokes the ferry spirit with a series of long howls into the Kyle Rhea while his masters are preparing to sail, and gets involved with (in the way of) the taking up of the moorings; Roxie, who’s fur is crinkly behind her ears, is still in her first week of the job and hasn’t quite got the hang of staying clear of the vehicles or the turntable mechanism yet. But she will.

We alighted on the Glenelg shore and a short journey to our lodgings, looking out onto Bernera Bay where, on a clear day, you can see the Isle of Eigg an outline like a moccasin shoe on the horizon. This bay will provide us with all the nutrients for a restorative break – from rejuvenating daily seawater dips to the abundance of fragrant yellow gorse – they say it’s a remedy for despair – to the protection afforded by a horseshoe of hillsides from everything but a breath of wind.

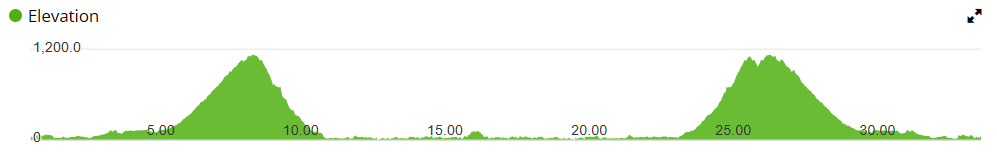

~ 2. GLENELG TO SHIEL BRIDGE, over MAM RATAGAN ~

FEELS LIKE cycling the col du Tourmalet in northern Spain

DISTANCE 33 miles

HEIGHT GAIN 2,806ft

ELEVATION PROFILE

Mam Ratagan is a mountain pass fêted by those in the know as one of the most beautiful roads in Scotland. It’s summit boasts a spectacular panorama of Loch Shiel and the Five Sisters hill range. Chocolates of Glenshiel is your destination – its hot chocolate is world-beating – but not before you’ve taken a detour up the shore road along the south coast of Loch Shiel (avoid the A87 to the north – it’s too busy for a contented cycle) for a view of crumbling Eileen Donan castle, with seals basking peacefully in the foreground.

I’ve been nervous about all our cycling this holiday – a combination of a shorter commute to work and an unpredictable problem with back pain have meant I’m deconditioned for an unrelenting Highland topography. I’ve dutifully done my warm up stretches and taken some painkillers but both have an unreliable track record, and if there’s one thing I hate more than struggling to cycle up a steep hill, it’s struggling to push my bike up it.

The start of the climb from Glenelg is gentle enough, through a picturesque glen that’s been beneficiary of a local rewilding project and lined with healthy young alder, hazel and oak, with an understory of buttercups, cotton grass, and bluebells as far as the eye can see. As the topography steepens higher up the glen there’s some delicious switchbacks to savour, roads carved into rock faces with greenery covering every fertile inch around you, thousands of delicate arms reaching hungry palms of chlorophyll as close to the sun as they can stretch, closely packed like Gorbals high-rise tenement wives leaning out of windows to hang their washing to dry. When human engineering crams life into the smallest conceivable spaces it becomes a slum; somehow nature makes it a wonderful ecosystem.

As you climb higher the plantation forest affords some welcome shade (though the bowels of this forest are denuded of life). Though the gradient has been reasonable so far it doesn’t let up and it’s taken a toll on my legs by the time I reach the top (having taken a few breaks to relieve my back a bit and pick up some roadside litter).

The summit was crowded with tourists disembarking tour buses proclaiming “the only way to discover Scotland is by bus” (what rubbish!) or private tour vehicles driven by stocky men in kilts and starched white shirts with long sleeves that must be uncomfortable in this heat.

The way down towards Shiel Bridge is incredible, a little steep for comfort in parts and my brakes squealed almost the whole descent, which was over far too quickly. The shore road is almost pancake flat and virtually traffic free, and overwhelms the senses with the salty lullaby of choppy waves hitting stony shores covered in seaweeds in various states of desiccation and a spectrum of colours from the deep tortoiseshell amber-brown of kelp fronds to the chewed-up tennis ball fluorescence of sea lettuce.

Fuelled by chocolate, the return leg is more ferocious, putting on the height over a mile’s shorter distance, and I admit it spat me off just a short 50 metres from the viewpoint, where the road is at it’s steepest and the fat middle fingers of Scot’s Fir flip up at you disparagingly from the roadside. I hopped back on just before the finish and unwittingly accepted a road of applause from a family of tourists. Back out the other side, the descent is up there with the greats; those same sweeping bends are a dream to fly down with the wind at your back and the formidable Cuillin ridge looking on from afar, almost keeping apace with the rusty-breasted stonechats that were flushed out of the undergrowth by the whirring of your freewheel hub.

~ 3. GLENELG TO ARNISDALE, and CORRAN HERRING PATH ~

FEELS LIKE coastal walks in Guadeloupe in the Caribbean, peeking through trees down to secluded bays and turquoise water

DISTANCE 25 miles

HEIGHT GAIN 2,364ft

ELEVATION PROFILE

I’ve not yet spoken about the ubiquitous sheep of Glenelg. They’re often walking along the road past our house, usually a mother with a lamb or two in tow, one of them hers and one a hanger-on. They doze in the shade of the coconut gorse bushes and sometimes rub up against them to satisfy an itch; they guard the small road bridge to the village with smug woolly grins; they will wander into your garden if even a sniff of an opportunity arises, but generally they avoid the beach. The walk past the barracks to the village is strewn with feathery blobs of moulted fleece. Little lambs panic when the people approach but they like the thrill of hanging around on the footpath. Sometimes, like the people do, they use the stepping stones to cross the brook. They’re LOVELY.

Our final ride passes through the village and clings to the coast, following the craggy contour of Loch Hourn to the remote settlement at Arnisdale. This route earned it’s spot on the tourist trail in part due to it’s being the setting for Ring of Bright Water, the story of a man who came to live in remotest Scotland with his pet otters. (I didn’t read the book myself but Hubs provided a précis, and it sounds like a book that hasn’t aged well, with themes of wildlife trafficking and animal-as-commodity that jar with a modern psyche that’s increasingly aware that man’s penury for dominion over nature may well soon be the source of his collective demise). Regardless, Sandaig Bay, a short walk from the roadside and the location of the author’s cottage and the monuments to both he and his latter pet otter Edal, is an idyllic archipelago of pristine beaches with brightly bleached driftwood and whiter-than-white shells. Further along the coast there are more islands, steep-sided with rainbow schists of rock, built like little forest-filled fortresses, perfect for otters to hide behind, no doubt. Because this is the otter metropolis; allegedly this is one of THE best spots in Scotland to see an otter.

Once through Glenelg village and past an impressive war memorial, the ascent starts in earnest; there’s nothing to fear if like me you’re most comfortable grinding out a steady beat in the saddle and in your middle gear on the front (if you have one, you’ll know what I mean). The road is gravelly and uneven in places, and can seek to unseat you where the shadows of tall trees dapple the road. Once at the top of this first main climb the height fluctuates, a big U-bend with a cattle grid at the bottom to sap all your momentum here, a low sweeping pass there between towering peaks that nonetheless wince in comparison to the ferocious wild vastness of great Knoydart to the south.

The walk itself is described on the Walkhighlands website – an old herring transport route from Corran to the village (why they weren’t brought up the loch by boat we’re not sure – perhaps those pesky otters would have got them). Having clambered through overgrown brush, had countless menacing encounters with ticks and made slow, ungainly progress across long stretches of pebble beach, we made it to the end of the route without a sniff of an otter sighting. We were feeling dispirited, but no sooner had we started to beat our retreat than a blip in the water, a little Loch Ness Monster appeared, just for a moment or two while it ate a piece of something, a crab perhaps, maybe even a herring, before giving it’s customary sign-off: a roll of the body and a flick of the tail, then back to the depths for a short while more.

There’s few surprises for the cycle back save for a short, sharp climb immediately out of Arnisdale village. The long descent back into Glenelg is a beauty if you like to test your mettle at speeds upwards of 40mph (the option exists to descend slower than this), and by the time you reach sea level you’ll likely be in the mood for a refreshment at the simply lovely Glenelg Inn.

*In the process of generating thousands of identikit hotspot tourist photographs at fairy pools and rock formations, the tourist pull is widely credited with gutting rural communities like Skye and it’s neighbours from the inside out, by creating a gold rush on land and property to be converted into holiday rentals, pricing out many would-be residents and creating local crises in key industries such as healthcare. (Judge what you will of our complicity in this). If you choose to holiday in a remote location like Skye or Glenelg, you can be a responsible tourist by:

- Driving and parking responsibly, and leaving your vehicle at home and taking public transport where you can

- Taking all your litter with you, and picking up other people’s litter where you see it

- Spending your money with local businesses

- Following local countryside codes such as remaining on footpaths near breeding sites for ground-nesting birds, and avoiding leisure activities that degrade the environment and rural economy, such as off-road driving experiences and grouse and wildfowl shooting

- Offering some of your time and money to benefit the community where you stayed, such as contributing half a day to a community project or donating to a local charity or food bank.

Wednesday 22 May, 2024